Did Jesus have facial hair? Unequivocally yes: Jesus had facial hair because the Bible says that he did. Isaiah 50:6 mentions Jesus’s beard when it describes his suffering thusly: “I offered my back to those who attacked, my jaws to those who tore out my beard; I did not hide my face from insults and spitting” (NET). From my perspective, this question should be open-and-shut. Recently, however, I have heard a few well-meaning Christians suggest that Jesus did not have a beard but instead was clean shaven—in spite of Isaiah 50:6.

These Bible students justify their claim of a beardless Jesus in several ways: by claiming that Jews of the second temple period were clean shaven, by claiming that early depictions of Jesus portray him without a beard, by claiming that we don’t see Jesus’s beard mentioned in the NT, by claiming that the Hebrew text of Isaiah 50:6 isn’t really talking about facial hair, and by claiming that the Hebrew text of Isaiah 50:6 contains a scribal error anyway—so instead we should use the Septuagint, which does not mention facial hair in the Greek version of Isaiah 50:6. At first glance, it might seem silly to discuss whether or not Jesus had a beard; “does it really matter that much?” you may wonder to yourself. But it does matter, because it involves the fulfillment of messianic prophecy.

As the Messiah (John 1:41, 4:25), Jesus perfectly fulfilled every messianic prophecy of the Old Testament. After his resurrection, Jesus taught his disciples, “These are my words that I spoke to you while I was still with you, that everything written (πάντα τὰ γεγραμμένα) about me in the law of Moses and the prophets and the psalms must (δεῖ) be fulfilled” (Lk 24:44 NET). I draw your attention to the word “must” / δεῖ: every single Old Testament prophecy of necessity had to be fulfilled.1 If Jesus had failed in fulfilling even one biblical prophecy, he would not have been the Messiah. Jesus uses the Jewish three-fold division of the Old Testament / Tanakh—Torah-Law, Nevi’im-Prophets, & Ketuvim-Writings (psalms etc.)—to emphasize that he fulfilled every messianic prophecy in the entirety Jewish Scripture.

When Jesus said this to his disciples, he was reminding them of something he had already told them prior to his crucifixion: “Then Jesus took the twelve aside and said to them, ‘Look, we are going up to Jerusalem, and everything that is written (πάντα τὰ γεγραμμένα) about the Son of Man by the prophets will be accomplished (τελεσθήσεται)’” (Lk 18:31 NET). Again, I draw your attention to the word “accomplished” / τελεσθήσεται: this word implies a) bringing an activity to conclusion (finishing / completing) and b) carrying out an obligation or demand (fulfilling).2 The messianic prophecies of the Old Testament were obligations or demands which Jesus was required to finish and fulfill. If even one of these prophetic obligations had gone un-accomplished, Jesus would have been an illegitimate messiah.

Jesus’s facial hair matters because we are dealing with the validity of our messiah and the reliability of our Scriptures: 1) do we know what Isaiah said about the Messiah, and 2) did Jesus fulfill everything that was written about him? Even if facial hair is trivial in itself, these two factors give this discussion serious importance.

It is my position that Jesus fulfilled everything about himself written in Scripture, including the phrase “they plucked out my beard” in Isaiah 50:6. Jesus had facial hair, because it was necessary for him to have facial hair, because Isaiah 50:6 was a prophetic obligation which Jesus was required to fulfill. Jesus definitely had a beard. In what follows, I will explain why I reject the claim that Jesus was beardless. I believe that this claim is built on faulty assumptions, a misunderstanding of historical data, and a misreading of key biblical texts.

Did Jews in Jesus’s day have beards?

Some people claim that Jews in the first century AD, generally speaking, were clean shaven because they were trying to fit in with the larger Greco-Roman culture, which promoted clean shaven-ness. It is true that most Greek and Roman men before, during, and after Jesus’s day were clean shaven; but there is strong evidence that Jewish men of this era grew facial hair unlike their Greco-Roman neighbors.

A. Edward Siecienski, a historian who has extensively studied ancient Jewish and Christian attitudes toward facial hair, writes,3

If Jews and Greeks shared similar attitudes about hair length, the same cannot be said about beards, for while the Jews continued to grow facial hair in observance of the law, most of their contemporaries did not, for “the practice of shaving, or at least of trimming the beard, prevailed in the Greco-Roman world, with occasional vagaries of fashion, from the time of Alexander the Great.” … By the time of Christ, and for several centuries afterward, Roman men were, by in large, beardless, portraying their heroes, emperors, and gods in similar fashion.

The OT law to which Siecienski alludes is Lev 19:27, which states, “Ye shall not…mar the corners of thy beard” (KJV). Those who advocate for a beardless Jesus frequently interpret this verse as referring to cosmetic shaving only, not as referring to clean shaven-ness. In other words, according to these brethren, Lev 19:27 does not require men to have facial hair or forbid men from being clean shaven; this verse only stipulates that, if a man has a beard, he must let it grow unhindered. A man must either be clean shaven or not alter his beard at all.

But this is not how ancient Jews understood Lev 19:27. In his research on ancient Jewish haircuts and shaving, Joshua Schwartz concludes,4

To cite one famous rule, the Bible forbade the marring of the corners of the beard (Lev 19:27). This was interpreted by the Rabbis as shaving with a (razor) blade against the skin…Eventually, shaving the entire beard and mustache with a blade was prohibited.

The [ancient] Jewish barber did not have a collection of razors such as those the non-Jewish one would have had. He did not shave his customers, but cut and trimmed hair and beards.

Jews of course did not go to the barber for a shave, but did frequent barbers for trims, that included beard trimming, and haircuts.

I recently heard one man say, “The Bible doesn’t say anywhere that men can’t be clean shaven.” According to Schwartz, however, devout Jews in antiquity did understand Lev 19:27 as prohibiting clean shaven-ness. Jewish men would not shave themselves at home5 or go to barbers for shaves; and Jewish barbers would not even own razors.

The Greek version of the OT known as the Septuagint (hereafter LXX) translates Leviticus 19:27 as “You shall not destroy the appearance of your beard.”6 The LXX’s wording arguably implies that any shaving of the beard was forbidden—including clean shaven-ness. To be clean shaven would certainly destroy the appearance of the beard, because there would be no beard to make an appearance! Thus Greek-speaking Jews who consulted a Greek copy of Leviticus would have come away with the idea that facial hair was mandatory for Jewish men.7

But apart from Levitical legislation about facial hair, other primary sources indicate that first century Jewish men wore beards, and in some cases cast clean shaven-ness in a negative light.

The Dead Sea Scrolls are a collection of ancient Jewish documents which were discovered in caves at Qumran (on the norther shore of the Dead Sea) between 1946-1956. Scholars date these documents between the third century BC through the first century AD8—so they provide an excellent window into Jewish culture shortly before and during the NT era. Although some of these texts are quite fragmentary, we see multiple mentions of facial hair. One document contains explanations for diagnosing skin diseases: “And the law for the scab of the head or the bea[rd, when the Priest shall see] that the spirit has entered the head and the beard seizing the artery, and the plague spreads from under the hair and turns its appearance to fine yellow.”9 Other fragments make mention of men having beards as part of physiognomic descriptions.10

Philo of Alexandria was a Greek-speaking Jewish author, well-respected in the Jewish community of his day, who lived roughly from 10BC to 50 AD. The dates of Philo’s life should catch our attention: he was born only a few years before Jesus, and lived for about twenty years after Jesus’s ascension. Around 39-40AD, emperor Gaius Caligula tried to set up a statue of himself as a god in the temple at Jerusalem. Caligula’s general Petronius had the sense to realize that doing this would cause the Judaeans to revolt, so he sent word ahead to the priests and governors to warn them about what was coming. Here is how Philo describes their reaction to the news:11

Smitten by [Petronius’s] words, we are told, as soon as they heard the story of the abnormal calamity they stood riveted to the ground, incapable of speech, and then while a flood of tears poured from their eyes as from fountains they plucked the hair from their beards and heads.

In 40AD the Jewish priests and civil rulers in Jerusalem had beards. Philo’s quote gives no indication that bearded priests or bearded governors was anything out of the ordinary. The unusual part of the story is the impending desecration of the temple—and they pluck their beards in response to this.

In one of his other writings Philo associates the removal of facial hair with other lewd practices common at Greco-Roman feasts.12

Some of them who are still boys pour the wine, while the water is carried by full-grown lads fresh from the bath and smooth shaven, with their faces smeared with cosmetics and paint under the eyelids and the hair of the head prettily plaited and tightly bound. For they have long thick hair which is not cut at all or else the forelocks only are cut at the tips to make them level and take exactly the figure of a circular line. They wear tunics fine as cobwebs and of dazzling white girt high up.

The serving-boys at these feasts were dressed up to look like girls—in delicate robes, long hair arranged in braids, and painted up with cosmetics and eyeshadow. To complete the effect, their facial hair—the last trace of their male sex—is removed. In what follows Philo goes on to describe the drunkenness, gluttony, and sexual debauchery common at these feasts: older male guests would have their way with boys who were just old enough to start growing facial hair, but who could not yet grow a beard. Again Philo’s statements here give no indication that shaving was normal for Jewish men of the first century; rather, Philo lists removing facial hair along with other gender-bending practices of the Greeks and Romans, and those who chose to imitate their wickedness.13

The Talmud also seems to describe Jewish men having beards shortly after the time of Christ (i.e., in the early second century) as a perfectly normal part of life. Tractate b.Berakhot 11a purports to record a conversation between Yishmael and Elazar ben Azarya, two rabbis who lived before 135AD. In this conversation, Elazar mentions the phrase “Your beard is full and suits you” as a compliment that someone might commonly make.14 Their conversation gives no indication that having a beard was an unusual occurrence.

Likewise b.Shabbat 152a purports to record a conversation between Rabbi Yehoshua ben Korha, a rabbi who lived before 135AD, and a eunuch. The eunuch insulted Yehoshua for walking around barefoot; in reply the rabbi said, “The glory of a face is the beard, the joy of the heart is a wife, and ‘the portion of the Lord is children;’ blessed be the Omnipresent who has denied you all of them, for a eunuch does not have a beard, a wife, or children.”15 Again, their conversation gives no indication that a Jewish man having a beard was unusual. In fact, it implies the opposite. If clean shaven-ness was common at this period, it doesn’t make sense to describe facial hair as a “glory.” Likewise, if most men did not let their beard grow, it makes no sense to use facial hair as a distinguishing characteristic between intact males and eunuchs. This strongly implies that the average adult Jewish male grew facial hair during this time.

Targum Pseudo-Jonathan takes a strong stance against shaving in its interpretation of Deuteronomy 22:5: “Neither fringed robes nor tephillin which are the ornaments of a man shall be upon a woman; neither shall a man shave himself so as to appear like a woman; for every one who doeth so is an abomination before the Lord thy God.”16 This again would seem to prohibit clean shaven-ness. Men’s faces naturally grow facial hair; women’s faces do not. The only way that a man can make his face “appear like a woman” is to be clean shaven.

But our data for Jewish beards is not just textual. Artistic depictions are less compelling evidence for grooming practices one way or the other, for reasons I will explain later. Nevertheless, we do have artistic depictions of Jewish men with facial hair from the first century AD. To give just one example, after the Jewish Revolt in 70AD (which culminated in the destruction of the temple) Roman emperors Vespasian and Titus issued coinage to celebrate their victory. Some of these Judea Capta coins depict a bearded Jewish soldier wearing a helmet, stripped partially naked with his hands tied.17

We thus have multiple points of data (both textual and material), in multiple languages (Greek and Aramaic), shortly before, during, and after the New Testament era—both of Jews discussing themselves and of outsiders (specifically the Romans) depicting Jews—which show that it was common for Jewish men during this period to have facial hair. It may be that some Jewish men shaved regularly like their Greek and Roman neighbors. I, however, am inclined to agree with Siecienski and Schwartz (quoted above) that Jewish men during the time of Christ generally had beards.

dont the earliest pictures of jesus show him without a beard?

It is true that our earliest depictions of Jesus portray him without a beard. That said, this in no way proves that Jesus was actually clean shaven.

For one thing, our earliest depictions of Jesus come from drawings on the walls of a house church at Dura Europos (Syria) or from paintings in the catacombs at Rome. These depictions are at least 200 years removed from Jesus. To put that in perspective, that is the distance between us and America’s sixth president John Quincey Adams. If we did not have access to photographs of Adams or literary descriptions of his appearance, our chances of accurately depicting him 200 years later are slim to none. Similarly, the artists at Dura Europos or the Roman catacombs had never seen Jesus; anyone who had seen Jesus was long since dead; and the NT & the earliest surviving Christian literature give no description of Jesus’s physical appearance.18 To be frank, it is simply naïve to assume that artistic depictions from two centuries later (depictions which, as you can see from the photos below, can sometimes be more sketch than portrait) are truly useful for reconstructing Jesus’s actual appearance.

For another thing, we should keep in mind that we are dealing with art. We simply cannot assume that these pictures were intended to be forensic representations of Jesus. They almost certainly were not. Any art historian will agree that there are a myriad of motivations and meanings can come to bear on an image. There are many reasons why these artists might have depicted Christ without facial hair, even though he did in fact have a beard. For example, as I have already noted the Greeks and Romans of Jesus’s day were generally clean shaven. The artists at Dura Europos or Rome could have depicted Jesus without facial hair so that he would look more like them—just as many white artists have portrayed “White Jesus,” black artists have portrayed “Black Jesus,” and Asian artists have portrayed “Asian Jesus.” There are other reasons why artists might have depicted Jesus as clean shaven, as I will discuss in the following section.

We cannot assume that Jesus actually was clean shaven simply because that is how the earliest pictures portray him. These artists lived two centuries after Christ—and we cannot assume that verisimilitude was even a concern to them, much less their chief concern.

was jesus depicted with a beard so he would look more like a pagan god?

Those who maintain that Jesus was beardless sometimes claim that Jesus was depicted with a beard so that he would look more like pagan Greco-Roman gods. The logic goes something like this: “In 326AD at the council of Nicaea, Constantine tried to blend Christianity with paganism so that he could unify his empire. In order to make Jesus more appealing to the pagans, Jesus began to be depicted with facial hair so that he would look more like Zeus, Asclepius, Serapis, or some other god.” There’s a lot to unpack here, so please be patient with my roundabout response before I come to the point.

With respect to the council of Nicaea, it is flatly false to say that this council had any regulatory influence over how Jesus was depicted. The canons and synodal letter from the council make no mention either of Jesus’s physical appearance or of how Jesus was supposed to be portrayed.19 It is likewise false to say that depictions of Jesus suddenly and completely switched from smooth to to bearded, as if this was the new Official Look™. Artists continued to depict Jesus without a beard for centuries after Nicaea.

The main purpose of Nicaea was to affirm the deity of Christ contra Arius and his followers, who denied that Jesus was God. Contrary to popular claim, Nicaea was not an attempt to marry Christianity with paganism. By the time we get to Nicaea, Christianity has undergone three centuries of persecution at the hands of the empire. Many of the bishops at the council had lived through the Great Persecution under Diocletian and Galerius; they knew people who had been martyred. These men would not have compromised simply because the emperor snapped his fingers.20 Blaming Jesus’ beard on Constantine or the council of Nicaea is, frankly, conspiratorial rather than historical. But let’s move on.

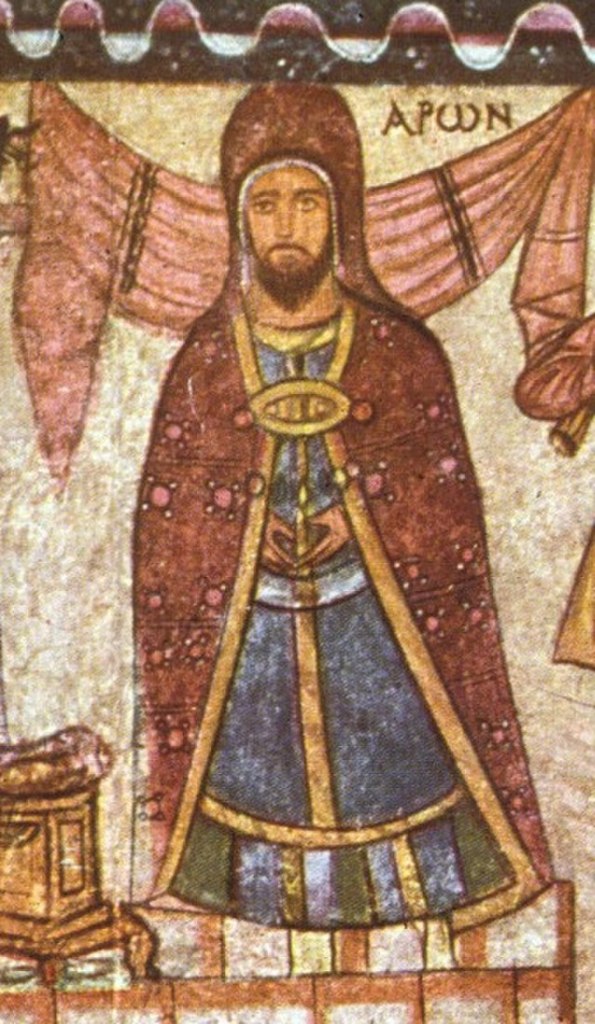

Just because Jesus was depicted with a beard, this does not automatically mean that people were trying to make him look like Zeus or some other pagan god. Such reasoning is overly simplistic. Were the Jews of the Dura Europos synagogue trying to make Aaron the high priest look like Zeus by depicting him with a beard?

Obviously not. We know from Ps 133:2 that Aaron had a beard—so when we look at depictions of Aaron, Zeus’s beard is entirely irrelevant. The same goes for Jesus: we know from Isa 50:6 that Jesus had a beard—so when we look at depictions of Jesus, Zeus’s beard is equally irrelevant.

Those who argue that bearded images of Jesus are pagan simply because they contain a passing resemblance to a false god should be careful with this type of reasoning, because it can just as easily be applied to portrayals of Jesus without a beard. Dionysus, Hermes, and Apollo were all Greco-Roman gods who are depicted without beards. Joan E. Taylor points out repeated similarities between images of Jesus and of these gods,21

The depiction of Jesus as a beardless youth or young man is found everywhere from the catacombs through to the high art of the sixth century…Hermes, the messenger of the gods, is presented as good-looking, often with curly, shortish hair and no beard…[Apollo] was often shown as an immensely good-looking, beardless and usually naked young man…Christ is explicitly depicted as Apollo (= Sol Invictus)…in a mosaic found under St Peter’s in the Vatican Mausoleum.

The reference to Hermes is especially relevant: in late antiquity, a beardless Hermes was frequently portrayed carrying a ram over his shoulder—so frequently that he was often called Hermes Kriophoros (“The Ram-Carrier”). One of our earliest depictions of Christ is of him carrying a lamb over his shoulders in a strikingly similar fashion. To quote Taylor again,22

One of the most widespread allegorical images of Christ in early Christian art is the image of the Good Shepherd. It is found constantly in the Roman catacombs, dating from the earliest periods of their use, across all of these underground mausolea. In this case it is clearly borrowed from the repertoire of Graeco-Roman [sic] iconography, associated with the god Hermes…We see this Hermetic Good Shepherd already in the pre-Christian parts of the catacombs in Rome, dating from the first century.

The image of a beardless man carrying a ram or sheep over his shoulders was such a common image in ancient Roman art that in multiple cases aren’t certain whether the art is depicting Jesus the Good Shepherd or Hermes the Ram Carrier. I could easily make a case that early Christian artists removed Jesus’s beard was so that he would look more like their common image of Hermes. Now you might think to yourself, “Pictures of Jesus carrying a sheep over his shoulders has nothing to do with Hermes! He is depicted as a shepherd because that is how the Bible describes him.” I agree. But by that same token, we should conclude Jesus having a beard has nothing to do with Zeus or Sarapis or any other god. He is depicted with a beard because that is how the Bible describes him.

In ancient Greco-Roman culture, some false gods had beards and other false gods didn’t. In a situation like this, Jesus was going to be similar to a false god one way or the other. It’s inevitable—and therefore insignificant.

But just for the sake of argument, let’s assume that Christian artists really were trying to make Jesus look like a pagan god—whether by giving him a beard or (more likely) taking his beard away. So what? This does not prove that early Christians were trying to mix Christianity with paganism. In fact, in certain situations it is proper and right to apply pagan descriptions of false gods to the one true God. Lest you think I’ve lost my mind, the Bible itself does this sort of thing repeatedly.

Babylonian mythology contained a story about Marduk smashing the head of a giant serpent; Psalm 74 uses similar imagery when it describes Jehovah as crushing Leviathan’s head. Baal was a Canaanite storm deity frequently described as riding on the clouds; Psalm 104 says that Jehovah “makes the clouds his chariot.” Ra was the Egyptian god of the sun, and Psalm 84 explicitly calls Jehovah “a sun.” In his sermon on Mars Hill in Acts 17, Paul quoted a poem to Zeus by Aratus23 to describe Jehovah as the creator—and Paul did this right after pointing to a pagan shrine “to the unknown god” and saying that Jehovah was the God worshipped there (albeit worshipped ignorantly).

The authors of Scripture were not trying to blend true religion with paganism in these cases; so why did they do it? I submit that they are engaging in literary one-upmanship. Under divine inspiration they applied these pagan descriptions to the Lord in order to show that Jehovah was the true God and all others were imposters. “You think Baal rides the clouds? No, Jehovah is the one who really rides the clouds. You think Zeus created humanity? Not a chance! Zeus didn’t do anything. Our God is the creator.”

I suspect that something similar is going on in early Christian artwork. Christian artists might have made Jesus look similar to various gods because they were trying to portray Jesus in a way that would have made sense visually to their culture. When Christian artists drew Jesus beardless with a lamb slung over his shoulder, they weren’t saying “Hey, let’s mix Jesus with Hermes.” They were saying “Pfff! You think Hermes is a good shepherd? No, Jesus is the Good Shepherd!”

We know that Jesus had a beard as a devout Jew—historically, because he was obedient to Lev 19:27, and because of Isa 50:6. But even if, in an alternate universe, Christian artists did add facial hair to Jesus so that he would look more like Zeus—what of it? Like it or not, doing this would be a perfectly biblical artistic strategy for calling Zeus a false god and exalting Jesus to his proper place of deity. If Paul can do it with poetry, early Christian artists can do it with paint.

As I stated in a previous section, this kind of artwork simply isn’t valuable for reconstructing what Jesus actually looked like because there are too many potential metaphorical meanings involved in artistic depiction. A picture is worth a thousand words, as the saying goes. There are all sorts of symbolic reasons why a Christian artist might have portrayed Jesus with or without a beard—and none of those reasons have anything to do with forensically representing what Jesus actually looked like as a historical person.

the nt never mentions jesus’s beard

Those who argue for a smooth Savior often point out that New Testament never mentions Jesus having a beard. As with other arguments, this might sound convincing at first; but upon reflection, the NT’s silence on Jesus’s facial hair turns out to prove nothing. It is true that the NT never mentions Jesus having a beard. But the NT also never mentions Jesus owning a razor, shaving himself, or going to a barber to be shaved.24 Since the NT is silent on both, it doesn’t prove anything one way or the other.

Now someone may say, “Well, because the NT doesn’t mention him having a beard, we shouldn’t assume that he had one.” To which I reply, “The NT also doesn’t mention Jesus having ears, a nose, toes, or hair.” We all assume that he had those things, even though the NT never mentions them—because it is natural for him to have them as a human. Likewise it is natural for Jesus to have a beard as a male. I reply again, “If I shouldn’t assume that Jesus had a beard because a beard is never mentioned, then you shouldn’t assume that Jesus shaved because shaving is never mentioned.” Those who claim a beardless Jesus and I are both coming to the NT with assumptions. I, however, approach the text with the assumption a) that Jesus had a beard like every other devout Jew of the first century (see above), and more importantly b) that Jesus had a beard long enough to be plucked like Isaiah prophesied would happen. Some people assume that the NT makes no mention of beards because nobody had them; but it is also equally probable that beards weren’t mentioned because everyone had them, and therefore it wasn’t worth mentioning.

A variant of this argument is that we don’t see the facial hair phrase of Isaiah 50:6 being fulfilled in the NT: the Gospels mention Jesus’s face being slapped, his back being beaten, his crucifixion and the parting of his garments (Isa 53, Ps 22)—but the NT makes no mention of Jesus’s beard being torn out. Again, this does not prove anything. If the OT makes a prophecy about Jesus, we can trust that it is true: the NT doesn’t need to give us an exhaustive list of every fulfillment about every prophecy. To give one example, the NT nowhere refers to Jesus as “Everlasting Father” or “Prince of Peace.” You can search the whole NT and never find those phrases. But I believe Jesus is the Everlasting Father and the Prince of Peace, even though the NT never applies this prophecy to Jesus.

We know that he had facial hair because of Isaiah 50:6, even though the NT does not mention it. There is much that the NT does not tell us about Jesus’s appearance, and so we shouldn’t be surprised that it also doesn’t mention this.

but isaiah 50:6 doesn’t say “beard”…

Some claim that Isaiah 50:6 does not prove that Jesus had a beard because זקן / zaqan, the Hebrew word for “beard,” is not present in the verse. “The Hebrew language has a perfectly good word for beard,” so the logic goes; “If Isaiah is talking about a beard, why doesn’t he use the word זקן?” While this sort of reasoning might sound compelling at first, this is a classic example of what I call the These Words Exactly fallacy. A person is guilty of the These Words Exactly fallacy when he insists that a specific wording be used, even though a different wording communicates the same concept.

I have repeatedly heard Muslim street-apologists fall into the These Words Exactly fallacy when they say things like “Show me one place in the Bible where Jesus says, ‘I am God; worship me.’” Jesus clearly claims to be God when he says, “Before Abraham was, I am” (John 8:58 & Exodus 3:14). Jesus clearly claims that he should be worshipped when he tells people to “honor the Son, just as they honor the Father” (John 5:23). Jesus clearly claims that he is divine and deserves worshipped when he refers to himself as the Son of Man who would come on the clouds of heaven (Mark 14:61-62, Daniel 7:13-1425). But none of these clear passages “count” for the Muslim street-apologist, because Jesus did not use the exact wording, “I am God; worship me.”

It is true that זקן is absent from Isaiah 50:6, but the wording Isaiah uses plainly shows that Jesus had a beard. This is why many modern Bible translations render this verse with something like “I gave…my cheeks to those who plucked out my beard.”26 But even if we use the KJV’s “I gave…my cheeks to them that pluck off the hair,” the meaning is still the same. The operative word here is not the presence or absence of זקן, but the verb מרט. This verb indicates a loss of hair, whether that be by naturally occurring baldness (Lev 13:40-41) or through some type of violent action (Neh 13:25). Ezra 9:3 uses מרט explicitly to describe the plucking out of a beard.

Isaiah says that Jesus had hair on his cheeks / jaws (לחי): if I am not allowed to call the hair on a man’s jaw a beard, I’m not exactly sure what I am supposed to call it. This verse might not use the exact word “beard,” but it clearly shows that he had one. Recall Lev 19:27—“Ye shall not…mar the corners of thy beard.” Gesenius’s lexicon glosses פאת זקנ as “the corner or extremity of the beard, the hairs upon the cheeks.”27 According to Isa 50:6, Jesus’s abusers tore out the very part of the beard which Lev 19:27 forbade Jewish men to remove. Jesus had a beard; in obedience to Lev 19:27, that beard had פאה / cheek-hairs; according to Isa 50:6, these cheek-hairs were plucked.

But already I can hear a couple objections.

Someone may say, “Isaiah 50:6 is the only verse that implies Jesus had facial hair—and we can’t build a doctrine off of one verse, because we are supposed to establish everything ‘in the mouth of two or three witnesses.’ So, in spite of Isaiah 50:6, we still don’t know for sure that Jesus had a beard.” The best refutation for this type of logic is to apply it consistently. Only one verse, Deuteronomy 22:5, says that cross-dressing is sinful; may a man wear a dress because God did not repeat himself? Isaiah 9:6 is the only prophecy which refers to Jesus as Prince of Peace; are you sure that he really is? Matthew’s Gospel is the only one to mention the wise men, the slaughter of the children at Bethlehem, and Jesus’s family fleeing to Egypt; Luke’s Gospel is the only one to mention the birth of John the Baptist, shepherds coming to the manger, and Jesus talking with the men on the road to Emmaus; John’s Gospel is the only one to mention Jesus turning water into wine and Jesus’s side being pierced with a spear. Should we doubt that all these things happened because they are only mentioned once? Surely not—and the same goes for Isaiah 50:6.

Someone else may say, “There is a difference between having hair on your face and having a beard. In Jesus’s day there was no Gillette or Norelco, so most men did not shave every day. Jesus could have had some hair on his face without having a full-grown beard.”28 But this is a distinction which does not actually prove anything. Even if I grant the point for the sake of discussion, it only acknowledges the hypothetical possibility that Jesus might have shaved on occasion. It certainly does not prove that Jesus ever did shave—much less that Jesus was clean shaven most of the time. In fact, as I’ve already shown above, devout Jewish men in Jesus’s day weren’t clean shaven and did not go to barbers to be shaved. This objection is only convincing when someone has assumed in advance that Jesus shaved regularly, but this is jumping to ahistorical conclusions.

Having a beard was common for Jewish men in Jesus’s day; Isaiah says that Jesus had hair on his jaw, and we have no hint elsewhere in Scripture that Jesus ever shaved. The most natural conclusion is that Jesus had a beard.29

mt, Dss, & lxx

I have also heard people argue that the phrase “pluck the hair” in the Hebrew Masoretic text (MT) of Isa 50:6 is a scribal error and thus was not part of the original wording of the verse when Isaiah wrote it. This argument is based on two claims: 1) our oldest manuscript of Isaiah, the Great Isaiah Scroll found among the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS), uses a different Hebrew word than the MT here, and 2) the Greek Septuagint (LXX) does not mention facial hair, but instead says “I gave my cheeks to beatings” rather than “I gave my cheeks to those who pluck the hair.” Because the authors of the NT regularly quoted from the LXX, these people further suggest that its reading takes precedence over the Hebrew Masoretic text in Isa 50:6.

The text-critical issues involved in this argument are somewhat complex, so for the sake of clarity I will state my conclusion up front. I completely disagree with this line of reasoning: I believe that “pluck the hair” is the correct reading of Isa 50:6 (i.e., what Isaiah originally wrote). The DSS and LXX do contain variant readings of Isa 50:6, but I believe that these variants either a) may not entail a difference in meaning, or b) if they do entail a difference in meaning, are explainable as textual corruptions.

Now let me explain why. I’ll deal with the DSS first and then address the LXX.

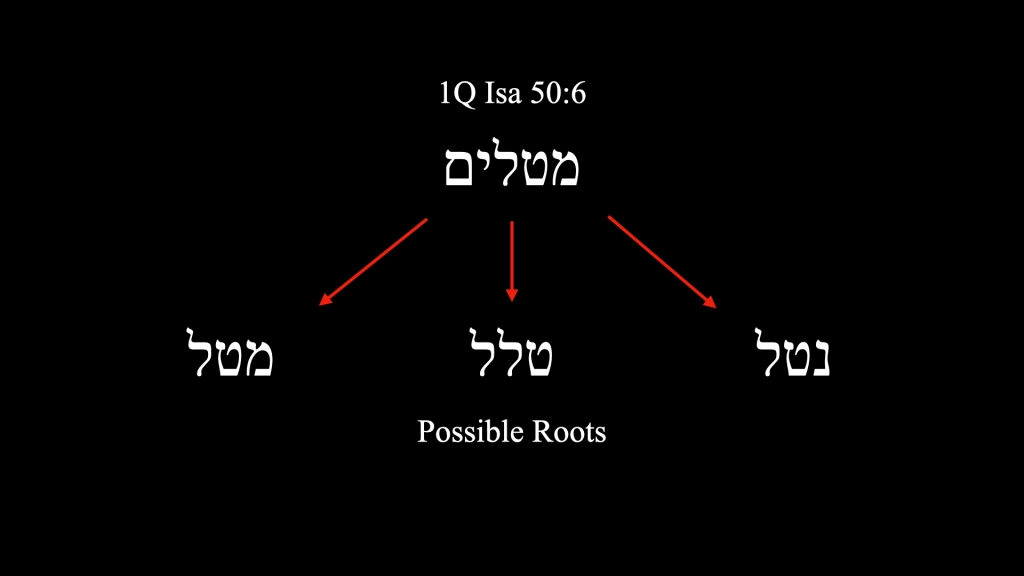

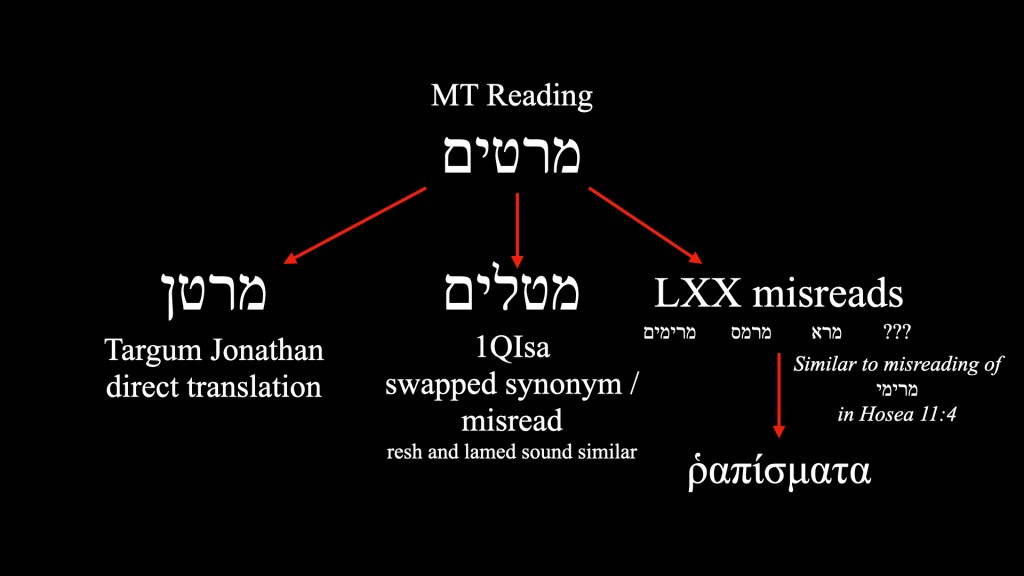

The phrase “those who pluck the hair” is a single word in the MT, מרטים. The Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsa) uses a different word, מטלים. Even someone who doesn’t know Hebrew can see that these two words look very similar and so one could easily be mistaken for the other. It is my contention that the scribe who produced the Great Isaiah Scroll made this mistake, substituting the error מטלים in place of the correct MT reading מרטים.

This difference between the MT and 1QIsa has perplexed scholars; according to Cyrill von Büttner,30 “Scholars have not come to a definite agreement on the meaning of the Qumran variant מטלים.” As best I can tell, scholars have suggested that this verb could be a participle form of one of three possible verbs. The proper translation of מטלים depends on which root we think it comes from.

For various morphological reasons it is unlikely that מטלים comes from the root מטל, so we can safely dismiss this option.31 This word refers to shaping iron by hammering, so if this were the root verb in question, it would produce the odd translation “I gave my face to those who forged.” Perhaps we could read this as metaphorically referring to being beaten, like a blacksmith beats the hot metal; but we must admit that this is an unusual way of saying it.

Multiple lexicons suggest that מטלים comes from the root טלל, but I don’t find this etymology convincing. The טלל root usually refers to covering something over; occasionally it refers to dew (because it covers a surface, Hg 1:10, Deut 33:13), and once it refers to putting a roof on a building (Neh 3:15).32 But the translations “I gave my cheeks to those who covered with dew” and “I gave my cheeks to those who made a roof” don’t make any sense—and so multiple lexicons suggest that טלל can sometimes mean “to injure” or “to cause to fall.”33

If this is the correct root, it would produce the translations “I gave my cheeks to those sho injured” (which makes good sense) or “I gave my cheeks to those who made me fall” (which is a little bit awkward, but still understandable). When we look at the examples of טלל conveying this meaning listed in the lexicon, however, only one example is cited—namely, the variant reading we are discussing in 1QIsa50:6.

In other words, the only place we know of in Hebrew literature where טלל might mean “to injure / cause to fall” is this variant reading in the Great Isaiah scroll. To my mind this makes this definition for טלל seem ad hoc, and therefore much less likely to be the correct etymology for מטלים in 1QIsa50:6. I would be more convinced of this etymology if it could be shown that “injure” was a common meaning for this verb—or at very least, if there were more examples than one. So, to my mind, טלל is also not the root for the Qumran variant.

This leaves us with נטל, which is the option that Cyrill von Büttner argues for. Unlike the “to injure” meaning of טלל, “the existence of which in Biblical Hebrew is questionable,” נטל is “a root firmly anchored in Biblical Hebrew as well as Aramaic and Rabbinic Hebrew lexicon.”34 I am inclined to agree with von Büttner that this is the most likely candidate for the etymology of מטלים. If this is the correct root, von Büttner says that it can produce two possible translations.

The first possible translation is “I gave my cheeks to those who caused to lift / take.” Perhaps we could understand this as the Romans or Jews forcing Jesus to lift and carry his cross. The only problem is that, depending on the context, נטל can refer either to making someone lift something in punishment (i.e., burdening them, Lam 3:) or to mercifully lifting something off of / for someone (i.e., unburdening them). So is Jesus turning his cheek toward the violent or the merciful? This word also regularly has “yoke” as an object, but there isn’t any object for this verb in Isa 50:6. To my mind, this translation is unlikely because of its awkwardness and ambiguity.

According to von Büttner, though, the verb נטל regularly refers to “taking away” facial hair in particular; he cites multiple examples of the verb being used this way in his article. Thus “it can be concluded that the word מטלים is the synonym of the Masoretic מרטים…The Isa 50:6a (1QIsa) text can be translated in the following manner: ‘I offered my back to those who beat (me), and my cheeks to those who force me to shave (my beard) / pull out (my beard).’”35 Unlike the other possible translation for the נטל root, this translation contains no awkwardness or ambiguity, and so I argue that it is the more likely candidate. If this is the proper translation, although the Great Isaiah Scroll technically has a different word than the MT, the meaning is entirely the same.

Now let’s move on to talk about the LXX. The LXX translates the relevant phrase as “I gave my cheeks to beatings,” using the Greek word ῥαπίσματα. I believe I know how this variant came about. The only other time that a word from the ραπισ* word family shows up in the LXX is in a translation mistake in Hosea 11:4. Whereas the MT says, “I became to them as one who eases the yoke on their jaws” (ESV), the LXX says, “I was to them as a man who beats on their jaws.” The Hebrew word for “one who eases” is מרימי—which bears a resemblance to מרטים. I suggest that a similar error is being made in Isa 50:6. The translator(s) of the LXX frequently made translation errors by misreading the Hebrew text, and Hosea 11:4 shows us that they were capable of misreading a Hebrew word containing the letters mem, resh, yod, and mem as some word rendered with ῥαπίζων. To my mind, it is not a stretch to think that they could have also misread a Hebrew word containing the letters mem, resh, tet, yod, and mem as some word rendered with ῥαπίσματα.36

Now someone may say, “The LXX makes no mention of hair in Isa 50:6. Since the LXX is the Bible that the authors of the NT quoted from, it should take precedence for our understanding of this verse—regardless of what the Hebrew says.” If this is the tactic that a person is inclined to take, I again hope that they will be consistent. The LXX version of Isa 9:6 does not call Jesus “Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace.” Instead, it calls him “Angle of Great Counsel.” Should the LXX take precedence here?—because if it does, it removes a clear reference of Jesus’s deity.37 There are many other passages in the LXX that read differently compared to the Hebrew; one should think long and hard before advocating that the LXX universally takes priority over the MT.

As our last piece of data, I mention Targum Jonathan—an Aramaic translation of Isaiah from around the time of Jesus. In this Aramaic version of Isaiah, 50:6 contains uses the word mrt / “pluck out the beard,” which comes from the same root as the Hebrew term מרט. Targum Jonathan thus supports the MT reading of Isa 50:6.

So, we need to consider what scenario caused these various readings to come about. If one reading can be shown to account for the production of the other variant readings, this is an argument in favor of its originality. As I see it, the MT reading מרטים successfully accounts for the generation of all the variant readings that we see in the DSS, LXX, and Targum Jonathan. Rather than labor the point with words, I show how I believe these variants were produced in a chart below.

Thus, to my mind, מרטים / “those who pluck the beard” is most likely to be the original reading of Isaiah 50:6. The variant in 1QIsa likely does not even entail a difference in meaning, but is merely a synonymous way of expressing the same idea as the MT; and the LXX reading ῥαπίσματα is unlikely to be original because it probably came from a misreading of מרט, just as the LXX reading ῥαπίζων in Hosea 11:4 came from a misreading of מרימי.

conclusion

Like his persecutors in the Sanhedrin, some are not satisfied until they have separated the Savior from his beard. Through a misreading of Scripture and history they try to pluck his face clean—but in the end, they are left grasping at straws. We have good historical evidence that Jesus had facial hair as a devout Jew in the first century AD. But even if we didn’t possess this historical data, Isa 50:6 clearly teaches that Jesus had a beard, objections notwithstanding.

As I have worked on this article, I’ve wondered to myself, “why does Jesus’s beard make some people so anxious? Why do they feel the need to make Jesus clean shaven? Could it be that we are allowing our modern traditions about facial hair to influence the way that we remember our Savior?” I do not have the answers to these questions, and I will not speculate on the motivations of those who advocate for a smooth faced Messiah. But I will close by stating my motivations.

I want to believe the Bible as it was originally written, and I want to think about Jesus as he really was: Jesus prayed, “Your word is truth”—and he said again, “You will know the truth, and the truth will make you free.” I wrote this (very long) article because I believe that Isaiah originally wrote “those who pluck the beard,” and I am anxious to see anyone change the wording of sacred Scripture (especially when that change seems to be motivated). I wrote this article because I believe “those who pluck the beard” is a prophecy that Jesus had to fulfill as Messiah. I wrote this article because I believe Jesus truly did have a beard.

All glory and praise be to our bearded Beloved—the worthy, whiskered object of all true worship, Jesus Christ our Savior.

- BDAG s.v. δεῖ, 213-214. ↩︎

- BDAG s.v. τελέω, 997-998. ↩︎

- A. Edward Siecienski, Beards, Azymes, and Purgatory: The Other Issues that Divided East and West (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023), 23. Emphasis added. ↩︎

- Joshua Schwartz, “Haircut and Barber in Ancient Jewish Society,” Jerusalem and Eretz Israel 10-11 (2018): 7, 28-29, 36. ↩︎

- Schwartz, “Haircut and Barber,” 33 “The Mishnah described a situation in which one cuts or shaves alone with no help. As it was also unlikely that many [Jewish] people were proficient in shaving, something generally forbidden, as we have seen, they might have removed, rounded off, or marred their beard with the help of someone else.” Emphasis added. ↩︎

- Lev 19:27b LXX: οὐδὲ φθερεῖτε τὴν ὄψιν τοῦ πώγωνος ὑμῶν. ↩︎

- The LXX’s rendering of Lev. 19:27 is especially pertinent for those who argue that Jesus was clean shaven while simultaneously championing the LXX as the Bible of the apostles and therefore superior to the Hebrew original as reflected in the Masoretic text. If the LXX truly is our standard, we must conclude that ancient Jews—including Jesus—were required to have beards under Mosaic law. ↩︎

- See here from The Digital Dead Sea Scrolls. ↩︎

- 4Q266, fr. 6, 1.5-6; trans. Geza Vermes, The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English (The Penguine Press, 1997), 148. ↩︎

- 4Q186, fr. 2; 4Q561; Vermes, Dead Sea Scrolls, 358-359. ↩︎

- Philo of Alexandria, Embassy to Gaius 223 (LCL 379: 117). ↩︎

- Philo of Alexandria, The Contemplative Life 50-52 (LCL 363: 143). ↩︎

- I occasionally hear some of my Oneness Pentecostal brethren refer to facial hair as “men’s make-up.” Philo would seem to do just the opposite and associate shaving with cosmetics. ↩︎

- b.Berakhot 11a. Read online here. ↩︎

- b.Shabbat 152a. Read online here. ↩︎

- Targum Pseudo-Jonathan on Deuteronomy 22:5. Read online here. Thank you to JC & MJ for putting me onto this reference and to AT for helping me examine the original Aramaic. ↩︎

- Joan E. Taylor, What Did Jesus Look Like? (New York: T&T Clark, 2018), 164-164, “The coins were designed to show the humiliation and subjugation of the Judaean people and thus represent them.” Notice how the Jewish man is bearded but the Roman emperor is not. ↩︎

- Taylor, What Did Jesus Look Like?, 1-2, 12-13. ↩︎

- Read the primary source documents for the council of Nicaea here. ↩︎

- The next two emperors after Constantine, Constantius II and Valens, supported the Arians instead of the Nicene bishops; but the Nicene bishops held to their conviction that Jesus was God, some even being exiled for refusing to cooperate with the Arians. This is strong proof that the men at Nicaea would not have mixed Christianity with paganism for political expediency. ↩︎

- Taylor, What Did Jesus Look Like?, 88-91. ↩︎

- Taylor, What Did Jesus Look Like?, 98-100. Emphasis added. ↩︎

- Or possibly a hymn to Zeus by Cleanthes. ↩︎

- Never mind, as I’ve already shown above, that devout Jews in Jesus’s day weren’t clean shaven. ↩︎

- Every time that the word פלח is used in Scripture it refers to the worship of a deity, most often of the one true God. ↩︎

- So CSB, ESV, LSB, NASB, NET, NIV, & NKJV, as well as the Louis Segond French version & the Reina-Valera Spanish version. These versions of the Bible are not reading a beard into the verse because of how Jesus is portrayed in film, as I have heard insinuated. ↩︎

- Gesenius, Hebrew and Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament, s.v. פאה. ↩︎

- I have also heard a variation of this argument which claims that Jesus was clean shaven throughout his life but began to grow facial hair after his arest because he was in custody and could not shave. The only problem with this is that Jesus was in custody for less than a day, and the average rate of facial hair growth is .5 millimeters per day—which accumulates to around half an inch a month. If Jesus shaved regularly, one day would not be nearly long enough for him to have facial hair to pluck. ↩︎

- I am delighted that I can use Ocham’s Razor to argue that Jesus had a beard! ↩︎

- Cyrill von Büttner, “A Note on מטלים in the Great Isaiah Scroll (Isa 50:6),” Revue de Qumrân 27, no. 1 (2015): 138. ↩︎

- Robert H. Gundry, “למטלים: Q Isaiah a 50,6 and Mark 14,65,” Revue de Qumrân 2, no. 4 (1960): 559. ↩︎

- HALOT, s.v. טלל I.

DCH , s.v., טלל I & III. ↩︎ - HALOT, s.v. טלל II.

DCH, s.v. טלל II. ↩︎ - von Büttner, “Note,” 138. ↩︎

- von Büttner, “Note,” 145. ↩︎

- To my mind, the nouns מרא (driving with a whip), מרירים (affliction), and מרמס (trampling) are all possible contenders for this proposed mix-up. ↩︎

- And, I point out for my Oneness readers, the only passage in Scripture which explicitly applies the term “Father” to Jesus. ↩︎

Well, my mind has not been changed. I am of the opinion, and have always been, that Jesus had a beard. This was an interesting read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As usual, you offer a well-reasoned argument in defense of your position. To me, it doesn’t matter one way or the other whether Christ routinely wore a beard. In my experience, those pro or con have been motivated to either perpetuate or get rid of a modern standard relating to facial hair. In my estimation, they fail to realize that the correctness of their view is not dependent on what Israelite men did in the biblical era.

One quibble, however. This apparent back-and-forth over the authority of the Septuagint is problematic. Orthodox Jews do not consider it to be authoritative, but if we’re going to cite it, we cannot be selective, lest we appear to be engaging in confirmation bias. Leviticus 19:27, in every English translation, excepting the CEV, Douay-Rheims and Wycliff, refers to the clipping or trimming of the edge of the beard (in several translations, trimming the beard itself). Indeed, The Complete Jewish Bible (endorsed by my Orthodox Jewish friends) states: ”You shall not round off the corner of your head, and you shall not destroy the edge of your beard.” And Rashi’s comments on said verse are:

In these instances, I think you pushed just a little too hard. The text in Leviticus does not forbid shaving, regardless how some Jewish authorities interpreted it. To argue their interpretation of that passage against the overwhelming consensis of other translations, while disregarding their interpretations of other passages which run counter to our beliefs is inconsistent at best. We cannot ignore the plain text in favor of any group, Jewish or otherwise, whose interpretations we do not accept carte blanche. Your overall argument is persuasive enough without these diversions.

Of course, you may object that I myself cite Jewish commentary, but I am not doing so against the plain reading of the text. Moreover, this citation is directly analyzing the implications of the direct text. It isn’t attempting to offer something that replaces the text with something it clearly doesn’t say.

LikeLike

Thanks for the read! Permit me, though, to respond to your quibble.

It was not my purpose to advocate for the authority of the LXX and I don’t think I quoted it selectively. My point re: Lev 19:27LXX was to show that Greek-speaking Jews in Jesus’s day would have *understood* the Greek text of that verse to prohibit clean shaven-ness—regardless of whether (the original Hebrew text of) the verse prohibited it or not. I wasn’t saying that the LXX was authoritative here, but merely that this is how the LXX would have been understood. And while it is true that *modern* Orthodox Jews do not consider the LXX authoritative, the LXX *was* used authoritatively by well respected Greek-speaking Jews in Jesus’s day (e.g., Philo).

In a sense, I would have been content to leave the LXX unaddressed here, but there were some (not myself) who were putting the LXX forward as authoritative. I spent so much time on the LXX because I was pushing my interlocutors to be consistent: “if *you* are going to use Isa 50:6LXX to suggest that Jesus did not have a beard, then *I* will use Lev 19:27LXX to prove that Jesus *had* to have a beard; if you like the LXX version of Isa 50:6, do you *also* like the LXX version of Isa 9:6?”——That’s what I was up to.

As for what Lev 19:27 (regardless of language) actually teaches, it may very well refer only to cosmetic shaving as opposed to clean shaven-ness. I’m willing to grant that point. However, I think I can make the case that even the Hebrew version of this verse does prohibit clean shaven-ness. Doesn’t being clean shaven “destroy the end of the beard and its borders” (to quote your Rashi back to you 🙂)? A person can’t be clean shaven *without* destroying these edges / borders. Thus, although I’m willing to grant the cosmetic-shaving-only interpretation, I’m not at all convinced that the rabbinic interpretation *is* against the overwhelming consensus of other translations. I would say that those translations could all easily be read in harmony with the rabbinic interpretation. The rabbis who offered a shaving-totally-prohibited interpretation were also “directly analyzing the implications” of the text, and so I disagree with the characterization that they were attempting to “replace the text with something it clearly doesn’t say.”

Of course, I’m not ignoring the plain meaning of the text—and I certainly *don’t* accept what the rabbis have to say carte blanche. I’m not even saying that we should follow their advice in our contemporary practice. My argument was purely historical: i.e., even if the rabbis were entirely off-base in their understanding of Lev 19:27, this *is* how they understood it, and so most Jewish men from that time period would have been bearded.

I don’t object at all to your use of Jewish commentary—though I’m not sure that Rashi is the best source to use, given that he lived in the 11th / 12th centuries. Most of the primary sources I quoted were much closer to Jesus’s time: the DSS are 3rd c. BC – 1st c. AD and Philo is 1st c. AD. Berakhot and Shabbat come from the 6th c., but refer to events which (allegedly) happened in the 2nd c.; and even these talmudic texts are still 500 years closer to Jesus’s time than Rashi.

But I’ve gotten carried away with a long reply, and I hope it doesn’t sound argumentative: just clarifying my position since you brought it up 🙂 Thanks again for reading! God bless!

LikeLike

Thanks for the clarifications. Given that it has been the practice of Jews to retain their knowledge of Hebrew, regardless where their travels have taken them, I’m not certain that Greek-speaking Jews were ignorant of the original text, even if they routinely used the LXX for everyday use. As a very rough analogy, many people today will routinely use the KJV for everyday reading, but will automatically consult other translations when researching a matter. We need evidence that Greek-speaking Jews asserted the superiority of the LXX as opposed to its being used authoritatively. In continuing my KJV analogy, it is often quoted authoritatively as well. Indeed, it’s mostly not a bad translation, so it is authoritative in many ways, but that of course doesn’t mean that it is superior to, say, the ESV overall.

Back to Lev. 19:27, I don’t at all see a requirement that men have a beard. Men in their community grew them, so I just don’t think it was an issue. The question would only arise if male gentile converts were clean-shaven. Since Romans were generally beardless, if there were evidence that the Jewish community required a Roman convert to grow a beard, that would be decisive proof that they considered the matter mandatory. Otherwise, I see said passage as addressing anybody having a beard. Since practially all men had beards, they were commanded to avoid shaping them. Indeed, I’m friends with Orthodox Jews who are clean-shaven. If some ancient Jews saw the matter differently, their views were not authoritative enough to be handed down as something binding.

Anyway, I don’t want to get into a pitched battle over this when there are far more important matters afoot. Thanks for the interaction. If you want the last word, have at it. I enjoy reading your blog.

LikeLike

I’m content to let you have the last word, brother 🙂 Thank you for reading!

LikeLike